No single sector in England is prepared for the impacts of climate change – with the last 10 years being a “lost decade” for government action, according to a new assessment from the UK’s climate advisers.

From 40C heat causing train tracks to buckle to fierce winter storms knocking out power supplies, climate change is already affecting every aspect of society, says a new progress report on adaptation from the UK’s Climate Change Committee (CCC).

As temperatures continue to rise, the UK will increasingly face both known and novel threats – including possible food shortages as extreme weather events overseas affect international supply chains and food prices, the report says.

But, despite worsening impacts, efforts to prepare for climate change are not increasing at the scale required, it adds.

The CCC identifies 45 outcomes that will be needed to prepare for climate change across key sectors, ranging from nature and food security to finance and telecommunications.

The government has not yet delivered on any of these – and only has credible policies and plans in place to deliver in the future for five of the 45 outcomes, according to the report.

The findings come shortly after an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report warned that – globally – far too little is being done to adapt to worsening climate impacts. With high levels of warming, limits to adaptation are likely to be exceeded, it added.

Below, Carbon Brief sums up the main findings of the CCC’s 2023 adaptation progress report and examines the risks identified for nature, agriculture and food security, energy, health and transport.

Worsening extremes

In its report to parliament, the CCC notes that the UK has faced a run of severe and often record-breaking extreme weather events since its last report in 2021.

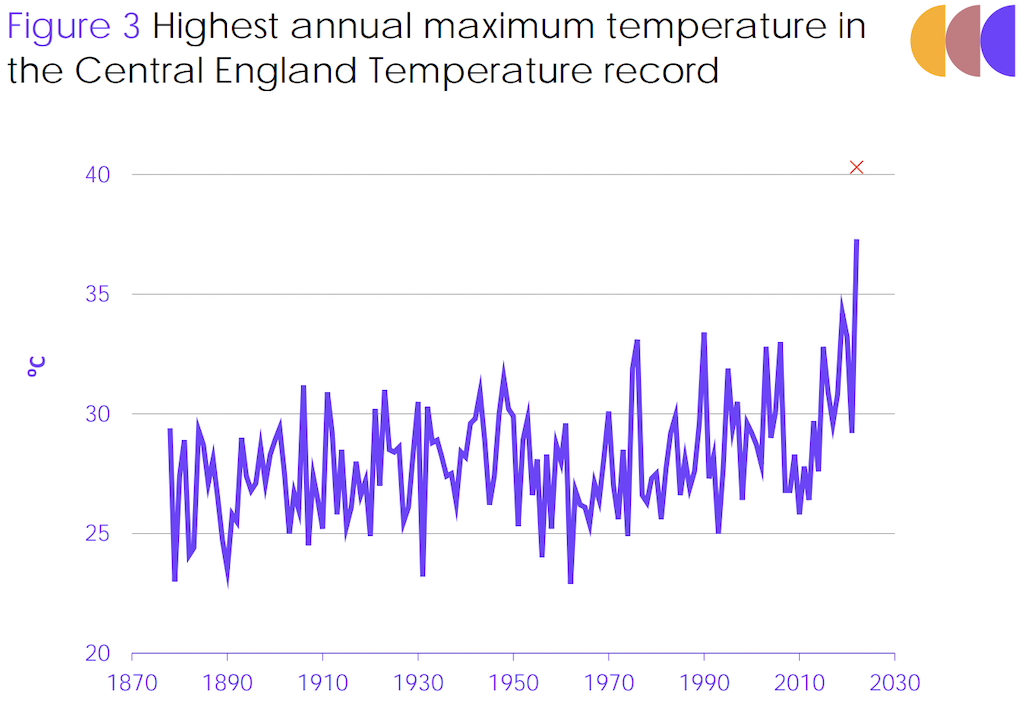

In 2022, the UK experienced 40C heat for the first time amid a widespread heatwave. The record far surpassed the previous high of 38.7C, set in 2019 (shown in the chart below).

The July to August heatwave led to a record number of heat-related deaths in England, the CCC says. The heat also caused power cuts due to conductors sagging and transformers overheating. At a press briefing, Baroness Brown, chair of the CCC adaptation committee, told journalists:

“[The heatwave] led to around 1,000 more heat-related deaths. 20% of operations were cancelled at the peak of the heatwave because our hospitals are not prepared for the very hot weather. We had rail disruption – overhead wires expanding, rail buckling, speed restrictions.”

As well as being hot, England’s 2022 summer was also the sixth driest on record – leading to widespread drought, according to the analysis. In East Anglia – a key region for producing food – it was the fourth driest.

The hot and dry conditions fuelled widespread wildfires. A new record was set in 2022 for the highest number of wildfires larger than 30 hectares observed in the same year, with fire services facing “major pressure” in mid-July, the report says.

As well as summer heat extremes, the UK has also faced more destructive winter storms. In February 2022, the UK faced storms Dudley, Eunice and Franklin in quick succession, causing “extensive damage to local electricity grids and flooding across the country”. The report adds:

“Storm Arwen left over one million customers without power and the north-east of Scotland experienced the equivalent of almost two years’ worth of overhead line faults in a twelve hour period.”

‘Lost decade’ for climate adaptation

The CCC usually reports to parliament on adaptation progress every two years, as required by the 2008 Climate Change Act.

However, this report looks back further – over the past decade. This allowed the CCC to take stock of the UK government’s first and second national adaptation programmes, which ran from 2013-2018 and 2018-2023, respectively.

It comes ahead of the third national adaptation programme, which is due to be published this summer.

Looking back, the report says there is “very limited evidence” that past adaptation programmes have led to action “at the scale needed to fully prepare for climate risks facing the UK across cities, communities, infrastructure, economy and ecosystems”. It adds:

“While the recognition of a changing climate within planning and policy is increasing, with some policy in most areas, it is clear that the current approach to adaptation policy is not leading to delivery on the ground and significant policy gaps remain.”

Speaking at a press briefing, Baroness Brown added:

“The last decade has been a lost decade in terms of preparing for and adapting to the risks – the risks we already have, and those that we know are coming.”

Also at the press briefing, CCC chief executive Chris Stark noted that one of the “oddities” about adaptation in the UK is that it is under the control of the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) – a ministry with relatively limited funds and influence. He said:

“That’s a sort of strange place in Whitehall for this stuff to be led.”

How different sectors are unprepared for climate change

For its assessment of adaptation progress, the CCC identified 45 outcomes that will be required if the UK is to prepare for climate change across key sectors.

The government has not yet delivered on any of these outcomes. And it only has policies and plans in place to deliver in the future for five of the 45 outcomes, according to the report.

The graphic below gives an overview of the lack of preparedness across key sectors, including nature, “working lands and seas” (agriculture and fisheries), food security, water supply, energy, telecommunications and IT, transport, towns and cities, buildings, health, community preparedness, business and finance.

On the graphic, the inner rings represent progress for policies and plans, while the outer rings represent progress for delivery and implementation. The level of progress is indicated through colour.

Below, Carbon Brief runs through the in-depth findings for some of the key sectors.

Nature

For nature, the CCC identifies three outcomes that will be needed to adequately prepare for climate change. These are that land, freshwater and marine habitats are all in “good ecological health”.

Healthy ecosystems are more resilient to climate change impacts such as droughts, floods and heatwaves, the report says. They hold “intrinsic value” and also offer important services to people, such as by soaking up CO2 from the atmosphere and helping to protect people from flood risk.

But the report finds there has been “insufficient progress” for delivering the outcomes for land and freshwater habitats – and “mixed progress” on delivering for marine habitats.

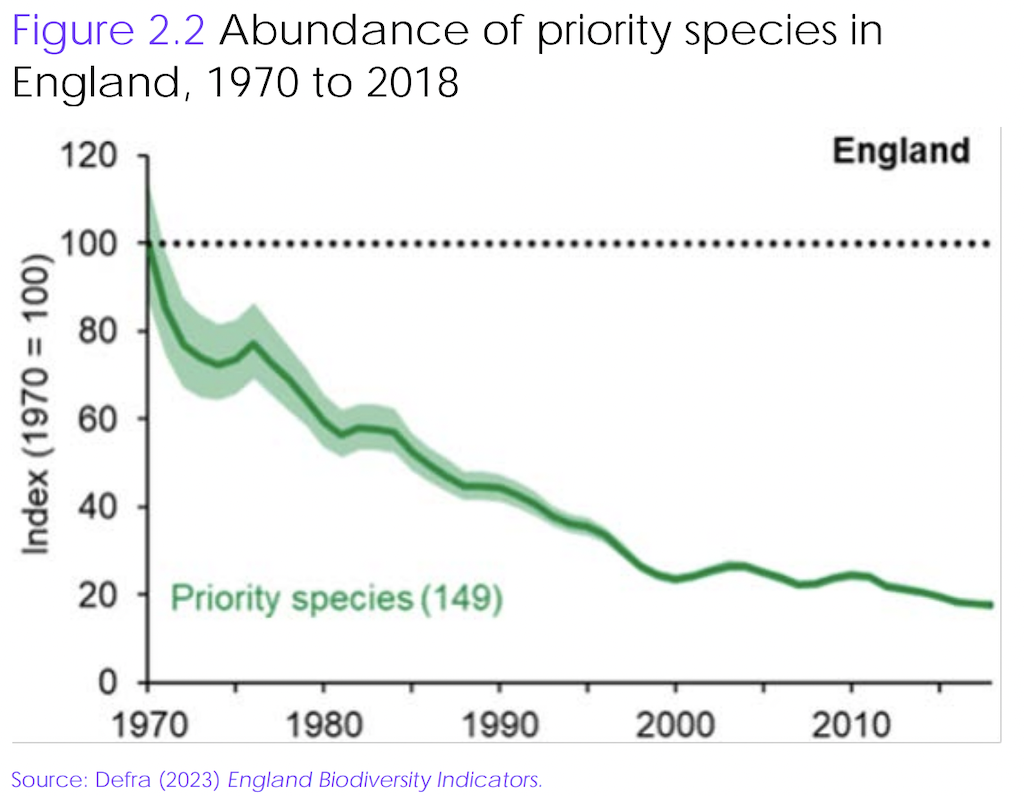

Between 1970 and 2018, the average abundance of the 149 species considered to be “important” for conservation in the UK fell by over 80%, the report says. (“Abundance” is a term for the number of individuals of a species in a given area.)

(Species of conservation importance are those that are threatened, in decline or those where the UK accounts for a significant proportion of the global population.)

The last few decades has also seen the abundance of priority species in England continuously decline, the report notes (shown on the chart below).

The CCC makes a number of recommendations for how the government should ensure nature is prepared for climate change, with most of these aimed at Defra.

This includes a recommendation for Defra to publish the full details of its long-awaited Environmental Land Management scheme, its post-Brexit replacement for the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy.

Agriculture and food security

For “working lands and seas”, the CCC identifies three outcomes that will be needed to adequately prepare for climate change. These include that the UK’s agricultural production, commercial forestry sector and fisheries and aquaculture sector are all “climate resilient”.

For agricultural production, the CCC says it is unable to evaluate progress on delivering the outcome due to “insufficient data”. It adds there are “insufficient policies and plans” in place to deliver in the future. The report says:

“Defra still lacks a plan to ensure the agricultural sector remains productive as the climate changes. Emerging details on the Environmental Land Management Scheme indicate some consideration of risks from future climate change, but this is not enough to strengthen the capability of agriculture to shift to more resilient production approaches.”

For forestry and fisheries, the report says there has been “mixed progress” in delivering the outcomes and there are “partial policies and plans” in place to ensure they are delivered in the future.

On food security in the UK, the CCC identifies two outcomes that will be needed to prepare for climate change. The first is that climate-related disruption to food and feed import supply chains is “minimised”. The second is vulnerability to food price shocks is “reduced”.

The report notes that the UK is “embedded within a complex international food system”.

Around 50% of food consumed in the UK is imported, the report says, with higher import shares of 85% for fresh fruit and 65% for other fruit and vegetables.

Many of the countries that the UK imports fruit and vegetables from are currently considered “water stressed” or “climate vulnerable”, the report says.

It notes that “the complexity and interlinkages of the food system allow climate change risks to be transmitted through trade, financial, cultural and political connections between countries”, adding:

“This means that an extreme weather event in one country can trigger an impact elsewhere in the world and risks can cascade across the globe in a complex way.”

In its assessment, the CCC says it was unable to evaluate progress towards minimising climate-related food disruption due to a lack of data reporting by large food companies. It adds there are “insufficient” policies and plans in place to ensure disruption is minimised in the future.

There is also currently “insufficient progress” on reducing vulnerability to food price shocks, the report says.

Among its recommendations, the CCC says that Defra should set out specifically how the government’s food strategy will ensure that food supply chains are resilient to climate shocks.

Energy

For England’s energy sector, the CCC identifies three outcomes that will be needed to prepare for climate change.

The first is that the vulnerability of England’s energy systems to extreme weather events is “reduced”. The second is that England achieves security of supply at a “system level”.

The third is that “interdependencies” between energy systems and other systems are “identified and managed”. (This is to reduce “cascading risks” for impacts from one system affecting another, the report says. For example, ensuring a risk to power supplies does not disrupt healthcare.)

The report says that changes to UK weather could lead to larger impacts on energy systems.

Some of these impacts are known, the report says. This includes the impact of heat increasing the electricity demand for air conditioning and leading to generation losses through the overheating of power station components.

However, some of these impacts are more “uncertain”, according to the report.

Such impacts include possible “wind droughts” – periods of low wind speeds – which could affect turbines. The report says high-resolution climate projections for the UK suggest there could be decreases to wind speeds in the summer under higher levels of global warming.

In its assessment, the CCC says there has been “mixed progress” on reducing the vulnerability of England’s energy systems to extreme weather events. It says there are “partial policies and plans” in place to ensure this outcome is achieved in future.

It adds there has been “mixed progress” on achieving a system-level security of supply and “limited policies and plans” in place to ensure this outcome is met in future.

In addition, there are “insufficient policies and plans” in place to identify and manage “interdependencies between energy systems and other systems, according to the CCC.

Among its recommendations, it says that the UK’s new Department for Energy Security and Net Zero should conduct a review of the energy system’s resilience to climate hazards. It also says the department should give the energy regulator Ofgem a clear mandate of ensuring the resilience of energy systems to climate hazards.

Health

For health, the CCC identifies two outcomes that will be needed to prepare for climate change.

The first is to protect the population from the impacts of climate change. The second is to ensure that people can access quality healthcare during extreme weather events.

England’s population is increasingly facing threats to their health from climate change, the report says.

For example, increasing frequency and intensity of extreme heat is increasing the number of heat-related deaths, as well as heat-related disease and illness. Heatwaves can “also create significant stress on the functioning of the health and social care system”, the report says.

Warmer temperatures are also creating more favourable conditions for vectors of infectious disease, with projections suggesting ticks and mosquitoes will have more suitable habitat in the UK in future, the report says.

Other hazards include flooding, which can lead to deaths and impacts on mental health, the report says.

In its assessment, the CCC says there is “insufficient progress” for delivering on protecting the population from climate change and ensuring access to healthcare is maintained during extreme weather events. It adds there are “limited policies and plans” in place to ensure this is achieved in the future.

The report notes that all of England’s health services have been instructed to create a “green plan” to help the NHS achieve its goal of reaching net-zero emissions by 2040. However, it says that this was a “missed opportunity” to incorporate long-term adaptation planning.

Transport

For transport, the CCC identifies six outcomes that will be needed to prepare for climate change. (The report notes that many of England’s transport systems already face threats from extreme weather events, such as floods, heatwaves and storms.)

The first is to ensure the reliability of the rail network in the face of climate change. The assessment says there has been “mixed progress” on delivering this but there are “credible policies and plans” in place to address it in the future.

The second is to ensure the reliability of England’s road network in the face of climate change. Again, the assessment says there has been “mixed progress” on delivering this but there are “credible policies and plans” in place to address this in the future.

It notes that the second Road Investment Strategy includes a “vision for climate resilience” and that the government agency National Highways has reported its climate change risk assessment and adaptation plans.

The third is to ensure the reliability of local roads. The assessment says there has been “mixed progress” on delivering this and there are “insufficient policies and plans” to ensure it is achieved in future.

“There is a lack of credible plans for local roads,” the report says.

The fourth is to ensure the reliability of airport operations. The CCC says it was unable to evaluate delivery on this because of a lack of available indicators. It adds that “partial policies and plans” are in place to achieve this in future – with 11 of the UK’s 40 airports putting forward plans for dealing with climate risks.

The fifth is to ensure the reliability of port operations. The CCC says it was unable to evaluate delivery on this too because of a lack of reporting from ports. It notes that there are “limited policies and plans” in place to achieve this in the future – with only four of the UK’s largest ports putting forward plans for dealing with climate risks.

The final outcome is to ensure “interdependencies” between different transport systems are identified and managed. The report says there is “insufficient progress” on delivering this and “insufficient policies and plans” to do so in the future.

Sharelines from this story

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- Platoblockchain. Web3 Metaverse Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.carbonbrief.org/ccc-england-has-lost-a-decade-in-fight-to-prepare-for-climate-change-impacts/